By Paul Reed, October 2023

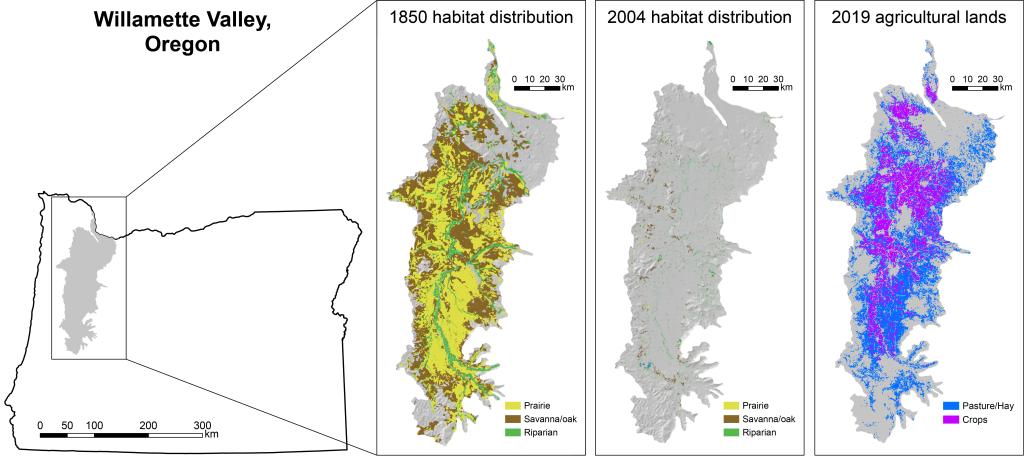

Admittedly, the Willamette Valley is not the first place that comes to mind when I think about bison, or even native prairies. The Great Plains seem much more obvious for both. Of course, you can find native prairies throughout the Willamette Valley. Best estimates, however, suggest that less than 10% of original prairie habitat remains. Hence the need for restoration. Bison, though? The American bison (Bison bison) is not known to have ever occurred naturally in western Oregon. You would need to travel back to the late Pleistocene (10,000+ years ago) to find evidence of even a direct ancestor, the antique bison (Bison antiquus), roaming the region. So, what’s the deal?

Most native prairie restoration efforts across the Willamette Valley focus on remnant and preserved sites with high conservation value. And that’s super important. But today, agriculture dominates the landscape. There are more than 170 agricultural commodities produced across 2+ million acres of working lands in the valley. Grass seed, pasture and hay for livestock, and hazelnuts are among some of the top crops that have replaced native prairie habitat. And these working lands aren’t going anywhere. Therefore, if we want to achieve grand, landscape-level restoration goals, we inevitably need to incorporate native biodiversity within this agricultural matrix.

Okay… So where do we begin? My Brothers’ Farm.

My Brothers’ Farm is a 320-acre farm in Creswell, Oregon (just southeast of Eugene), owned and managed by the Larson family. Over the past decade, the family has been transitioning their working lands from a 40+ year history of conventional annual ryegrass seed production into a diversified orchard, ranch, and riparian forest, where they raise pigs and bison and grow organic hazelnuts, apples, and other crops. Within their bison pastures, they aim to develop a rotational grazing system with sustainable perennial forage, while also supporting biodiversity and providing additional ecosystem services such as pollinator habitat. One way to achieve these latter goals is by incorporating native prairie species into their pastures.

Native prairies are a disturbance-adapted ecosystem that evolved with fire. When restoring degraded grasslands to native prairie habitat today, typical methods include the use of herbicide, prescribed burning, and mowing to reduce existing vegetation and provide opportunities to replant with native vegetation. In an organic agricultural setting, however, not all these tools are available. Instead, carefully managed rotational grazing may serve as a valuable disturbance regime.

Through a USDA-NIFA postdoctoral fellowship with the Hallett Lab at the University of Oregon in 2021, I began partnering with My Brothers’ Farm on an experiment to test whether we can use bison grazing as a tool to introduce native prairie species to working lands.

You might be wondering: why bison? Well, some anecdotal evidence suggests that their herding behavior is different from that of other livestock such as cattle, which could influence the intensity of grazing. There is also some thought that their cloven hooves help to aerate and restore soil health better. Truthfully, however, there seems to be little scientific evidence to illuminate much of a difference in grazing effects between bison and cattle. Instead, it really comes down how the grazing is prescribed and managed: graze heavy and hard if you want to create bare ground opportunities for new seeding activities, but graze at shorter intervals and less intensely if you want to maintain the existing community and allow forbs to flower and persist. For My Brothers’ Farm, the choice to raise bison simply came down to it being a niche market in the Willamette Valley.

For our experiment, we were interested in the following questions:

- Can grazing reduce annual ryegrass enough to allow native prairie species to establish from seed?

- Can natives coexist when seeded in conjunction with a traditional perennial forage mix?

- Can natives persist long term with regular grazing?

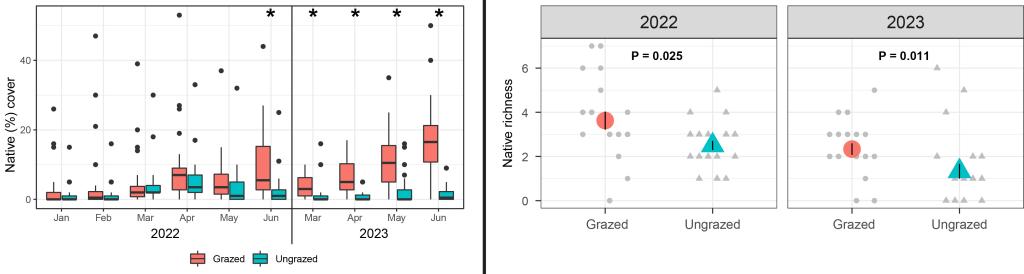

Between 2020-2021, My Brothers’ Farm retired a 36-acre field from annual ryegrass seed production and began grazing their herd of bison in it. The field was divided into six paddocks in which the bison would rotationally graze for 3-5 days at a time (alongside hundreds of additional acres across the farm). In fall 2021, My Brothers’ Farm began transitioning the fields to perennial pasture by seeding half of each paddock with a traditional perennial forage mix. Simultaneously, I established grazing exclusion zones in each paddock, set up 48 plots (4 m2 each) across experimental treatments for grazing (grazed/ungrazed) and the background pasture community (ryegrass/perennial forage), and seeded each plot with 10 native prairie species. In spring 2022 and 2023, I estimated plant cover and measured species richness in each plot.

Through two growing seasons, we found that there was greater native cover and richness in grazed relative to ungrazed plots, and these effects persisted through time. Additionally, being seeded in conjunction with a perennial forage mix (versus being seeded into just annual ryegrass) had no effect on native species success. These results suggest that not only can we use grazing as a disturbance tool for restoration, but we can incorporate native species into working lands and provide win-win opportunities for both conservation and agricultural objectives.

Since I joined IAE in summer 2022, we’ve been building upon these promising results with plans to scale up restoration across an entire six-acre paddock. The paddock we’re restoring is dominated by annual ryegrass as well as another common problematic weed, false dandelion (Hypochaeris radicata), which provides minimal forage value. The field also suffers from poor soil health and compaction from decades of conventional annual ryegrass production, so we’re incorporating additional management actions to alleviate current conditions and prep for future seeding.

Just this month, the farm is completing a final disking treatment for the annual ryegrass and false dandelion and will seed a cover crop mix designed to suppress weeds through winter and spring 2024. Our plan is to terminate the cover crops in spring 2024 through heavy grazing, followed by another round of disking in the summer, before seeding a suite of native prairie species and more perennial forage across the entire paddock in fall 2024.

Ultimately, the pasture community we develop will not exactly resemble true “remnant” native prairie habitat. But that’s okay. Our goal here is different: we’re aiming to enhance native biodiversity across a working landscape that, in recent history, has been dominated by monoculture grass crops. Along the way, hopefully we’ll create more habitat for pollinators, improve soil health and pasture quality, and cultivate new partnerships to continue expanding the restoration portfolio.

I am grateful to the Larson family for taking an interest in restoring native prairie species to their farm and for collaborating on this project. I would also like to thank Lauren Hallett for her mentorship, Joey Decker for helping collect data, and Ian Silvernail, Amy Bartow, and Tyler Ross from the USDA Plant Materials Center in Corvallis for visiting the site and offering invaluable suggestions on the restoration plan. This project is funded by USDA-NIFA postdoctoral fellowship #2021-67034-35136 and transfer award #2021-67034-38825.