Untangling soil nutrients, prairie communities, and golden paintbrush

|

| This summer golden paintbrush were thriving at a reintroduction site at William L. Finley National Wildlife Refuge (photo by Caitlin Lawrence). |

Golden Paintbrush, Castilleja levisecta, is an endangered herb which is endemic to the Pacific Northwest. While it was once abundant in British Columbia, Washington, and Oregon, there are only eleven known natural populations remaining. Golden paintbrush has been lost in many areas due to habitat conversion, and no natural populations remain in Oregon. Efforts to create new populations of golden paintbrush are ongoing throughout its natural range, and many of these reintroductions have shown great success.

|

| Haustorial connections between a golden paintbrush and host plant can be seen on the roots of these plants (photo by Katie Jones). |

In one experiment currently in progress, we are testing the effect of altering plant community diversity and soil nutrient availability on the success of golden paintbrush. One interesting characteristic of golden paintbrush is that it is a hemiparasitic plant. What this means is that while it does not require a host plant to survive, it can benefit from neighboring plants by attaching belowground to other species roots and extracting water, nutrients and secondary compounds via direct root-to-root haustorial connections. One way we can help recover this species is to provide it with host plants that it can parasitize. For this experiment, the first treatment was to seed some plots with multiple host species to see if increasing the diversity of the community will increase golden paintbrush reintroduction success. We combined this with a second treatment of altering the soil nutrient levels, both increasing and decreasing them relative to unmanipulated controls. Varying the levels of nutrients provides a test of how golden paintbrush will perform under different levels of available nutrients. This is interesting not only as a restoration technique but also could aid in the selection of future sites for reintroduction, and provide insight into how the success of golden paintbrush could be impacted by nutrient enrichment which could occur though nitrogen deposition from nearby urban areas, fertilizer runoff, or from other sources. Additionally, experimental plots without golden paintbrush were included in this experiment. Comparing these to the ones with golden paintbrush will allow us to test the effect that the reintroduction of paintbrush has on the community, since golden paintbrush has been absent from these communities for some time.

|

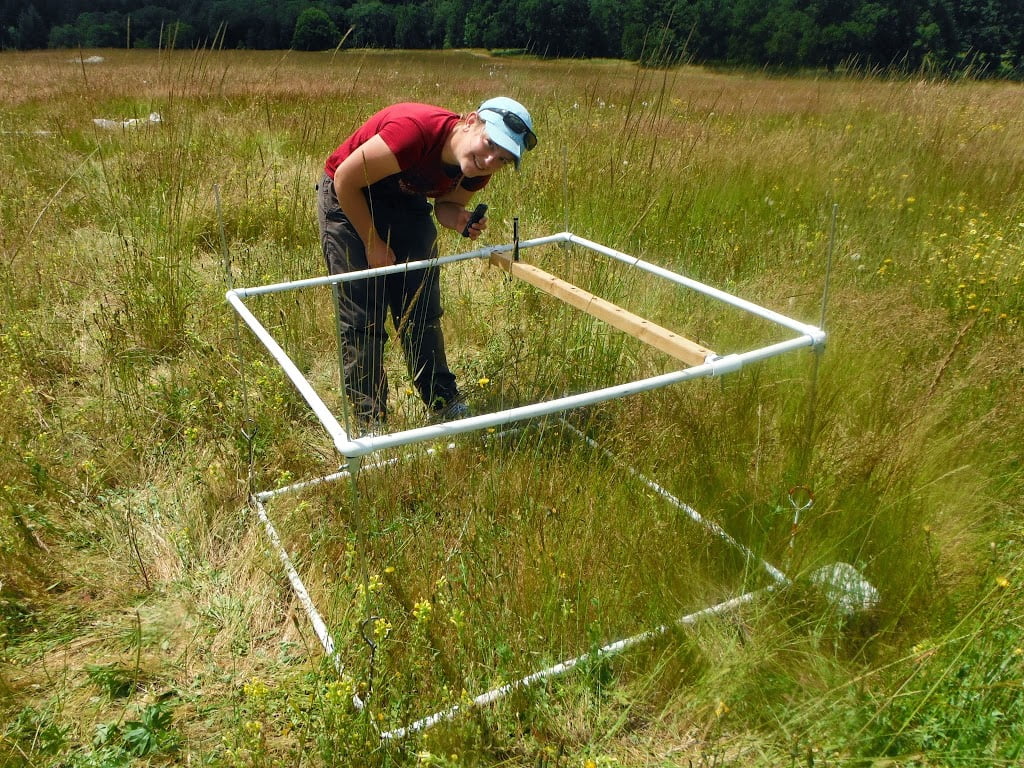

| Caitlin Lawrence using the point-intercept method to estimate percent cover of vegetation in her plots (Photo by Tom Kaye). |

The first data were collected on this project in the spring and summer of 2013. What we’ve seen so far is that in plots where the level of nutrients in the soil was lowered through the addition of carbon, less golden paintbrush seedlings established than in the control or fertilized plots. The number of seedlings was the same in control plots and fertilized plots, but the plants were larger where we added fertilizer. We also saw differences in the plant communities caused by nutrient availability. Reducing nutrients in the soil reduced plant productivity by 20% to 31%, depending on the site. Adding nutrients caused productivity to increase by 44% to 59%. Nutrient availability also changed the relative abundance of invasive plants. Weed abundance dropped by 20% to 31% when nutrients were reduced, and increased 0% to 12% when fertilizer was applied. In 2013 we didn’t see differences between plots seeded with the additional host species and those that weren’t seeded, but since the hosts were still very small this year, we expect to see a greater influence when we collect data again in 2014.