Rubus bartonianus (Bartonberry)

Say hello to one of our newest species of interest here at IAE, Rubus bartonianus (Bartonberry, RUBA). This diminutive little berry is a member of the genus Rubus, which encompasses a wide variety of aggregate fruiting berries such as blackberries, raspberries, marionberries, and salmon berries (to name just a few). Rubus bartonianus grows exclusively on the steep talus slopes and rocky river banks of Hell’s Canyon, along the Snake River and it’s tributaries. Currently, this plant is endemic to just 45 river miles! Rubus bartonianus has seen habitat reduction due to damming, fire, rock slides, livestock grazing, and competition with the exotic Rubus ameniacus (aka Himalayan blackberry). It’s shrinking habitat range has led to it being considered “imperiled” as well as a federal species of concern.

Through our efforts we hope to explore the best methods for germinating and propagating R. bartonianus seeds, which can then be out-planted in historical R. bartonianus habitat along the Snake River. Currently, it is unknown what the optimal conditions are for R. bartonianus to germinate. Many Rubus species require scarification and/or stratification of the outer seed shell before they can germinate. In the wild, many of these species rely on birds to eat them for this process to happen. The strong acids in the animal’s stomach effectively scarify the hard outer shell, leaving the actual seed intact after passing out of the digestive system. In lieu of force-feeding a bunch of birds these seeds and waiting for nature to do its business we are looking into other ways to recreate this scarification. We are currently exploring three different scarification treatments: sulfuric acid, bleach, and mechanical sanding.

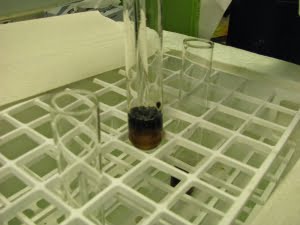

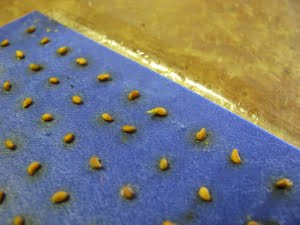

Top left:Erin Gray applying sulfuric acid to a batch of RUBA seeds. Photo credit: Emma MacDonald. Top right: The acid burns the seed shells, leaving the outer layer black. Photo credit: Emma MacDonald. Bottom left: After chemical scarification the burnt outer shells must be mechanically scraped off. Photo credit: Emma MacDonald. Bottom right: Up-close view of a scarified seed. Photo credit: Erin Gray.

We are also trying to determine the optimal cold and warm stratification periods for this species. Many Rubus species have been seen to germinate better and faster after enduring a warm stratification followed by cold. Naturally, these conditions are met as the maturing seed endures a warm summer and early fall; then a cooler, wetter period through winter. To find R. bartonianus‘s optimal warm and cold periods, we are subjecting treatments to 30 days of warm followed by 120, 90, and 60 day cold-stratification periods.

Once stratified, the germinated seeds will be planted in the greenhouse until they are ready to be taken back to Hell’s canyon for reintroduction. Our main goal for this project is to determine the best method(s) for propagating Rubus bartonianus.We hope to use this information as well as the products of our experiments to replant R. bartonianus in the wild and maintain the species historic range within the Snake River Valley. Funding for these efforts was provided by the Vale District Bureau of Land Management, and we thank botanist Roger Ferriel for his support. Thank you to Dr. Kim Hummer and Dr. Sugae Wada, at the USDA ARS National Clonal Germplasm Repository in Corvallis, who have offered their expertise in germination of Rubus species and use of their laboratory facilities.

National Clonal Germplasm Repository. Photo credit: Erin Gray.