Restoring Fire, Restoring Prairies

by Llew Whipps, August 2025

A common notion about habitat restoration is that it restores natural ecological cycles and function to wild areas harmed by humans. Broadly speaking, this is true. But in the Willamette Valley, much of our work centers on restoring landscapes that actually rely on human intervention – in the form of burning – to thrive.

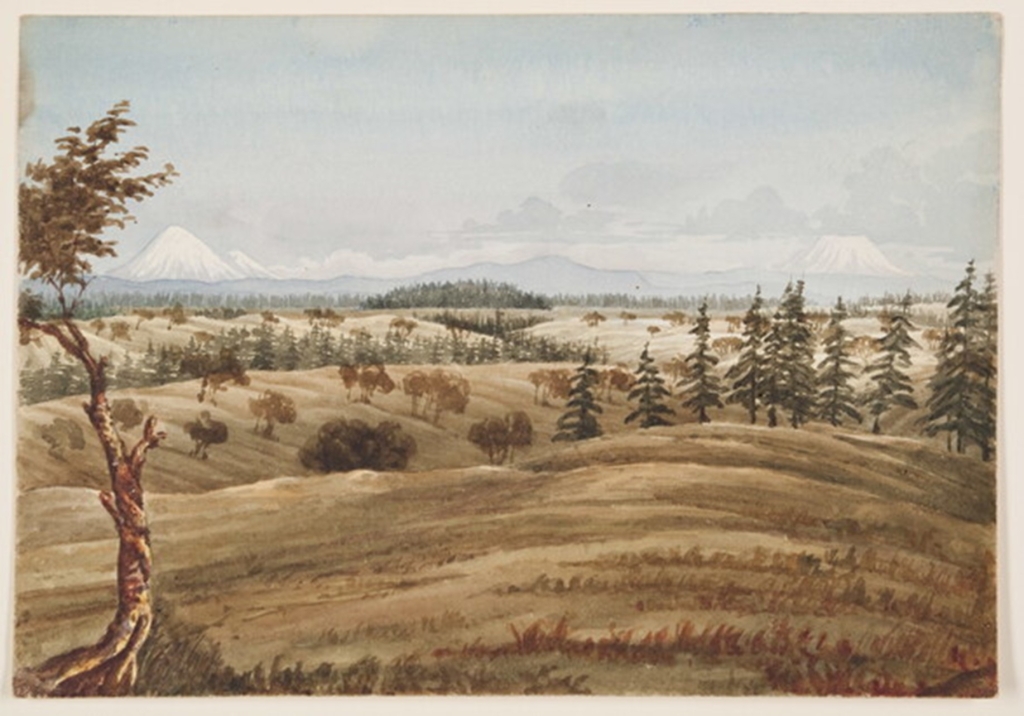

Before Euro-American colonization, Indigenous peoples used fire at large scales to manage land, burning every three to five years to maintain food, fiber, and other resources. This maintained open prairies where fire-resistant Oregon white oak could thrive. These prairies are anchor habitat for hundreds of species and define the Willamette Valley’s character to this day.

Without fire, prairies and savannas fill in with trees and shrubs, many of them invasive species. Oaks get shaded out by fast growing, large conifers, and insect and disease outbreaks become more common. Thatch builds up and wildflowers become less abundant. These pressures are common throughout the valley, and restoration practitioners have devised many strategies to wrest prairies back from encroachment. However, to restore early seral habitat it’s not enough to bring back the plants and animals that once lived there. We also need to restore the processes that maintain this habitat.

Recently at IAE we have been working hard to incorporate ecological fire into our restoration work. Seven restoration team members have Firefighter Type 2 certifications, multiple sites are scheduled to burn this fall, and we actively engage with partners to include fire in their long-term stewardship plans. However, in a populated region with fragmented land and varying burn regulations, burn planning needs to be done thoughtfully and inclusively. Making things more challenging, most sites have gone decades or centuries without fire, which means a lot of ‘pre-burn work’ is required before fire can be used safely again.

One way people have overcome the complicated logistics and expenses of prescribed fire is by forming Prescribed Burn Associations, or PBAs. PBAs are community-based networks that bring landowners, organizations, and volunteers together to share equipment, knowledge, and resources for burning. In the spirit of barn raisings, PBAs help people get to know their neighbors and feel more connected to the place they live.

This past year, IAE, along with partners at Oregon State University, Greenbelt Land Trust, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, and landowners experienced with fire, began efforts to start a PBA in our area – the Mid-Valley PBA. We had our first kickoff event in July, which brought people together to learn, share ideas, and get to know each other. Now, we are working hard to sort out governing documents, permits we’ll need to begin burning, and to schedule skill building workshops for volunteers. And we are building our base! If you live in the mid-Willamette Valley and want to be involved or learn more about prescribed fire, you can fill out this interest survey to get on the mailing list.

I’m particularly excited about burning as a community effort because I have seen first-hand what a great experience it can be. Last year, I started participating on prescribed burns in the south Willamette valley and Central Oregon, where burning is more common. I have had the opportunity to burn in grasslands, woodlands, and ponderosa pine forest. At every burn, I saw how people checked in with each other and collectively kept us safe, noticed how the fire responded to conditions, and felt the excitement of seeing land receive fire after so long.

Returning fire to the landscape after a long pause will take patience and flexibility, but I am excited about what it can bring to our restoration work and to our sense of community and place. Rebuilding a relationship with fire is about imagining what we want life in this valley to look like deep in the future. Fire is part of living here, and when we use it thoughtfully, we can turn it from a threat into a tool, a teacher, and a joy.