Mulford’s milkvetch research update

It takes a full day of driving from western Oregon to reach the closest populations of Mulford’s milkvetch (Astragalus mulfordiae) in the Owyhee Uplands of Malheur County. This rare species occurs in scattered populations in rangelands of Oregon and southwestern Idaho, mostly on sandy soils on rolling hills, flats and near the Owyhee and Snake Rivers.

This is cattle country, with a long history of people living on the land. But what is the effect of cattle on populations of this plant that is considered endangered by the state of Oregon and a species of concern by the US Fish and Wildlife Service? Are cattle and sheep a threat to the species’ survival, or is rangeland grazing compatible with viable, sustainable milkvetch populations?

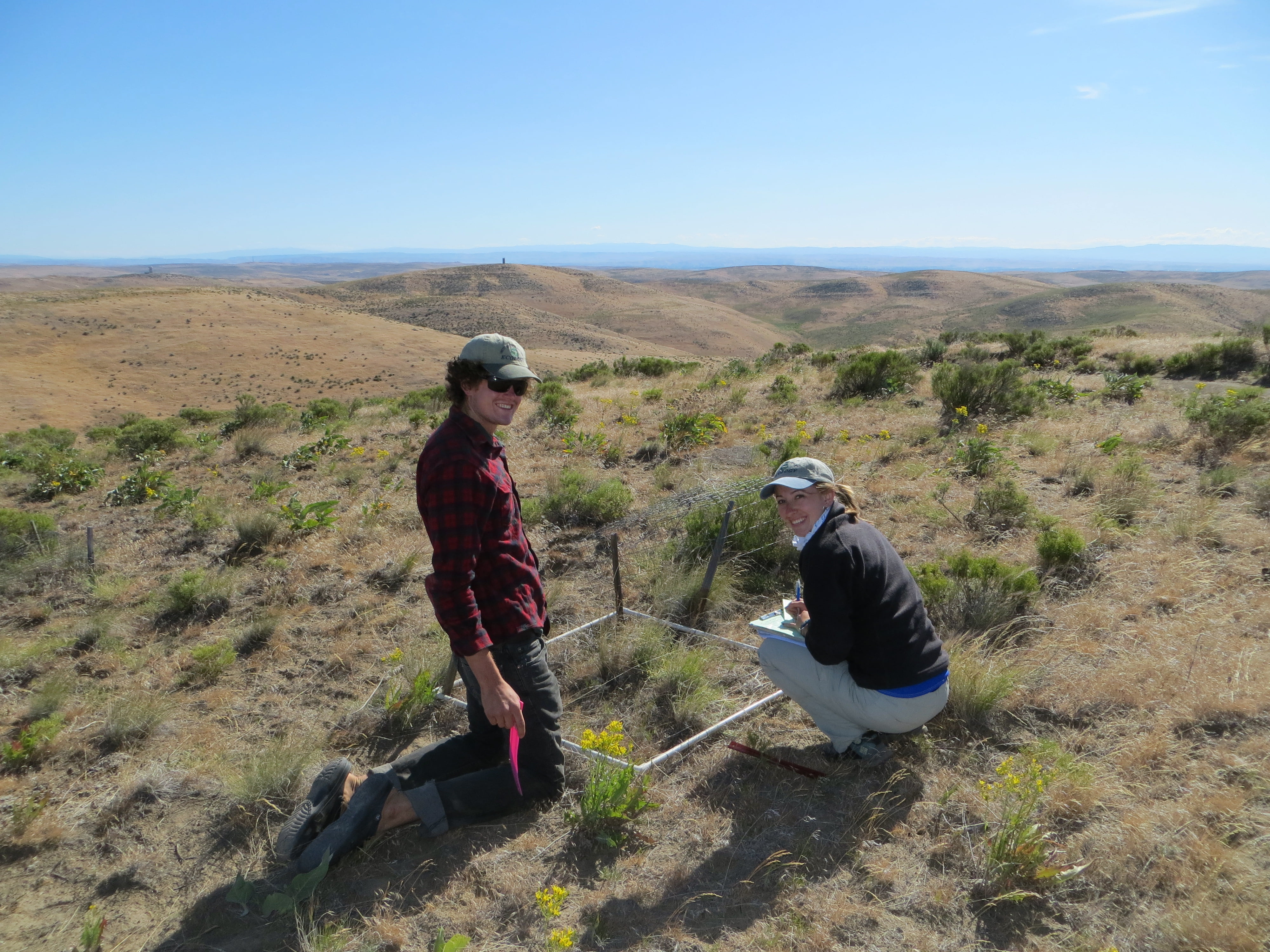

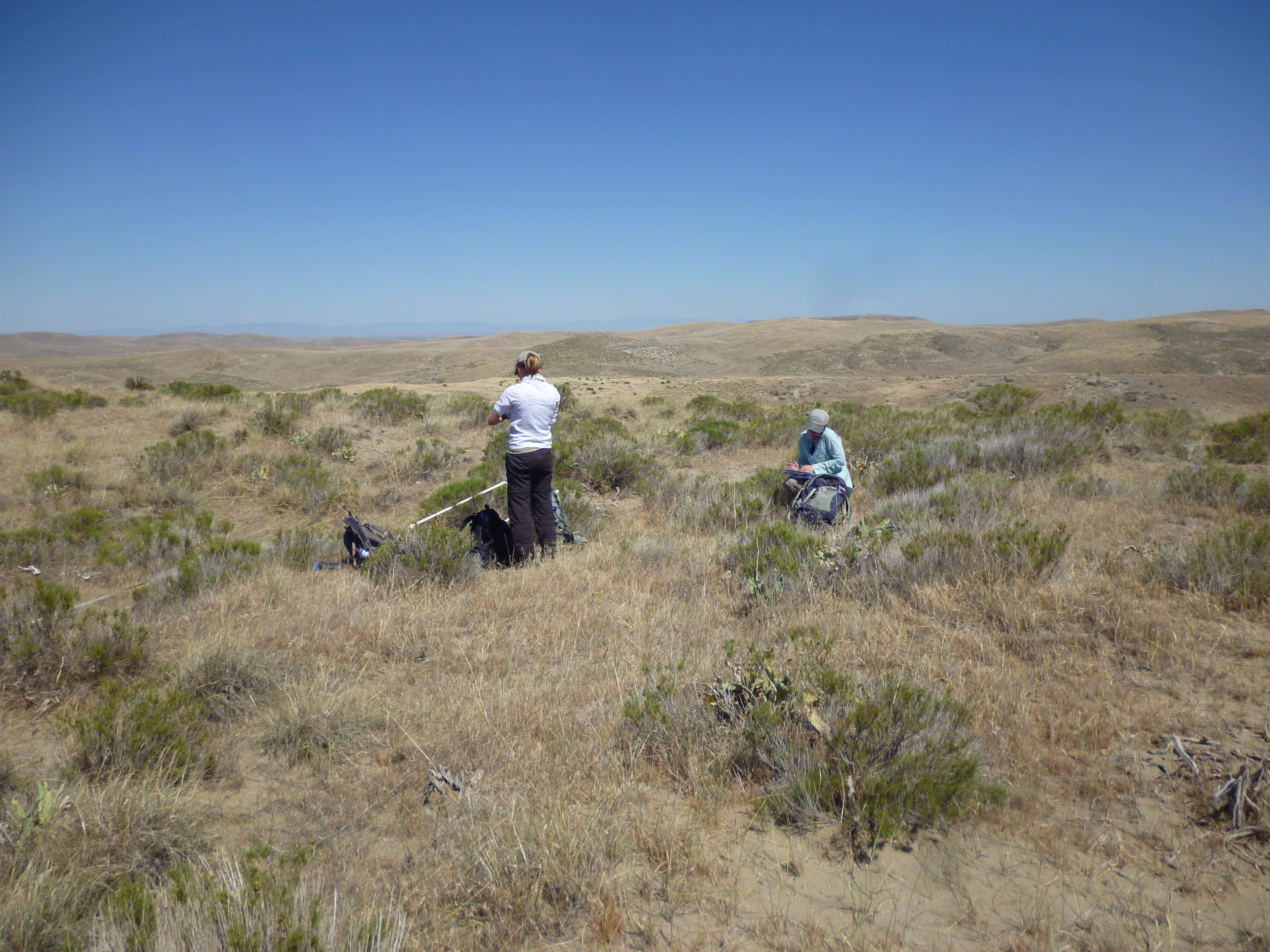

Since 2008, IAE biologists have partnered with the Bureau of Land Management on a long-term study to evaluate the effects of cattle and sheep on the species, and document population and habitat trends in wild populations. The project involves comparing the growth and survival of plants in plots protected from grazing with plants that are open to animal use, and this design is repeated at six different sites in Oregon. Protected plots are covered with a hog wire cage to prevent ungulate grazing, while still allowing for rain, sun, and smaller animal activity. Biologists map, measure and record animal grazing on all the plants in the plots each year.

So far, caging plants to protect them from large herbivores has had localized effects. For example, in 2016, plants had greater diameter on average in cages, but this effect differed from site to site. At one site where the effect was conspicuous, Snively Creek, caged plants were 40 cm wide while plants exposed to grazers were only 22 cm wide. The same pattern was true for reproduction. Again at Snively Creek, plants produced an average of 221 fruits in cages, but just 41 in uncaged plots. These preliminary results from the study suggest that grazing with livestock may have direct negative effects on this species at some sites and some years, but the effects are variable and complex.

In the course of this project investigators have witnessed an overall decline in the number of Mulford’s milkvetch plants at all sites, as well as an increase in the abundance of competitive invasive plants. The decline in plant numbers has been consistent across the landscape, and was particularly pronounced in 2014. In 2010, all sites were dominated by native vegetation except for South Alkali, but by 2015 all sites were exotic-dominated. Invasive plants such as cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum), stork’s bill (Erodium cicutarium), and Russian thistle (Salsola tragus) have steadily increased, which may be an indirect effect of cattle use or other disturbances.

Over the course of this study, weather at the research sites has tended to be drier than the long-term average, which may have contributed to the observed declines. However, winters of 2015 and 2016 were wetter than previous years and more similar to long-term normals, which could explain an uptick in the number of new plants noted in 2015 and 2016. Despite the recruitment of seedlings seen in 2015 and 2016, the decline in Mulford’s milkvetch population numbers observed in the preceding years coupled with the decrease in their size and annual variability in reproductive effort suggest that continued monitoring will be essential for managing for persistence of this species, especially when facing current and ongoing climate changes. In the coming years we will be looking to compare our long-term data set on Mulford’s milkvetch populations in Oregon with data collected in Idaho. In 2017 we will collect the sixth year of consecutive-year data in this long-term project.

Restoration

Research

Education

Contact

Main Office:

4950 SW Hout Street

Corvallis, OR 97333-9598

541-753-3099

info@appliedeco.org

Southwest Office:

1202 Parkway Dr. Suite B

Santa Fe, NM 87507

(505) 490-4910

swprogram@appliedeco.org

© 2025 Institute for Applied Ecology | Privacy Policy