Making more milkweeds for monarchs: breakthroughs in milkweed seed germination

IAE staff, June 2018

Monarch butterflies are declining at an alarming rate, in part due to the widespread loss of milkweeds, the plants on which all monarchs depend. Without milkweeds, monarch butterflies have no place to lay their eggs and feed their larvae.

One action people can take to help monarchs and other pollinators is to plant and cultivate milkweeds broadly on the landscape, from urban locations to wildlands. It’s as simple as germinating the seeds and planting them.

But there’s a catch: milkweed seeds can be tricky to germinate.

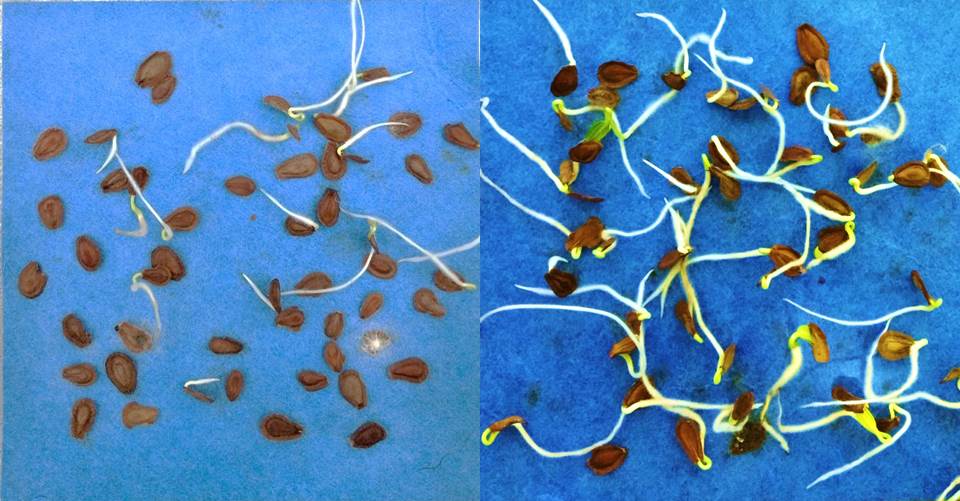

Some authorities suggest that milkweed seeds germinate well with no special treatment: just provide water, light and a warm environment and off they go. But others recommend giving the seeds a cold and moist environment (a process called cold stratification) for period of a few days to months, followed by warmth to promote germination.

To resolve this apparent contradiction and improve propagation success for milkweeds, researchers at the Institute for Applied Ecology conducted germination tests on several species of Asclepias, the genus of plants to which milkweeds belong. The results were published last month in the open access journal AoB Plants.

“We found that some species need two or more weeks of cold stratification to release their seeds from dormancy, while others had no dormancy at all,” said project PI and IAE Executive Director, Dr. Tom Kaye. The research group included Dr. Matt Bahm of IAE’s Conservation Research Program and Isaac Sandlin, a graduate student in the Department of Botany and Plant Pathology at Oregon State University.

The researchers also found that the need for cold stratification to break dormancy and allow seeds to germinate varied not just between species, but across populations of the same species.

In addition to conducting germination tests on six Asclepias species, the group comprehensively reviewed the literature on milkweed seed dormancy and germination, providing a summary of germination information for over 20 milkweeds. Some populations in at least 15 species have improved germination with cold stratification.

Stacy Moore, who leads IAE’s Sustainability in Prisons Project in six western states, grew showy milkweeds for two National Wildlife Refuges in eastern Oregon and Idaho. “Some of our seeds just wouldn’t germinate. At first we were baffled, but then we suspected the seeds might be dormant,” said Moore. This experience was one of the motivations for the current research by IAE. “After we started using cold stratification, germination success was huge.”

“We hope these results help those who propagate milkweeds get much higher germination and produce many more milkweed plants for monarch conservation,” said Kaye.

This work to unlock the secrets of milkweed seed germination and promote monarch butterfly conservation was supported by the US Fish and Wildlife Service as well as the Institute for Applied Ecology.