Emerald Ash Borer Invades Oregon — What to expect

By David Cappaert

September 1, 2022

In 2002, entomologists (I was one of them) in Michigan were presented with a striking iridescent beetle that had emerged from a stack of ash firewood. We knew that it was a buprestid -- a jewel beetle. Not a surprise; these beetles are wood borers, generally found in stressed, even dying hardwoods. But the species--Agrilus planipennis--was new, a migrant from China. Everything known about A. planipennis (newly named as the emerald ash borer, or EAB) at that point came from a short discussion in a Chinese journal. Within the next several years we learned a lot more, as emerald ash borer essentially eliminated ash on city streets and in natural landscapes across Michigan. The infestation spread to Ohio, Illinois, Pennsylvania ... and now to most of the US, including, in 2022: Oregon.

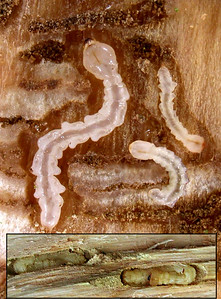

The emerald ash borer is a phloem feeder: the larvae carve serpentine galleries in the thin layer through which the tree transports nutrients. Eventually, enough larvae will girdle the tree, which then dies. At the stand level, the destruction is nearly total. I have consulted with city managers facing the loss of 10,000 street trees, and removal/replanting costs of over $10M. I have walked through ash-dominant natural areas (black ash in swamps, green ash in riparian areas) that had become ghost forests. The only conceivable benefit of this ecological disaster is the (temporary) explosion of food for woodpeckers. Otherwise, it has been said, without hyperbole, that emerald ash borer is the most destructive forest pest in North America. The impacts are manifold. The nursery trade in ash collapses. Neighborhoods lose the environmental, aesthetic, and psychological benefits of street trees. The character of natural ash habitats is transformed in unknown directions.

As of this writing, emerald ash borer has been detected in Oregon in the Forest Grove area. Trees at the site where it was first discovered this summer were immediately cut and chipped, but based on experience from the east, it is likely that the infestation is not isolated – and indeed, recent surveys have discovered more affected trees in the area. In Michigan, there were early efforts to eradicate the pest: expensive operations to harvest and chip trees in one city were barely underway before a new infestation was reported in the next county over. So, it is likely that we are on a trajectory to see widespread infestation in the next several years, and potentially the functional loss of ash (at least in the Willamette Valley) within the decade. I would love to be wrong about this. Meantime, here are few questions that might be relevant.

How do you recognize an Emerald ash borer infestation? Initial attacks are often in the tree canopy, so that is where you will see the signs. Woodpecker attacks are the clearest kind of evidence, because healthy ash trees are very unlikely to host prey for woodpeckers. Infested trees will also exhibit progressive dieback, from the top down. In later stages of infestation, they will often have luxuriant basal growth and epicormic shoots. The D-shaped exit holes from emerged adults, if on an ash tree are diagnostic, but usually these are not seen until other symptoms are evident.

What kinds of trees are susceptible? Ash (Fraxinus spp) are the only emerald ash borer hosts. In Oregon, Oregon ash, Fraxinus latifolia, is the only native species; other species are found in landscape plantings. Among ash, there are some features of resistance--particularly for Asian species that co-evolved with Emerald ash borer; however all Fraxinus species are at risk.

Will any trees survive? There are two slivers of hope. One is that juvenile trees (<2" diameter) are spared; after the initial wave of emerald ash borer passes, these trees will mature in an environment with far lower pest pressure. There is some evidence from Michigan that ash will persist at low population density. A second possibility is the potential for emerald ash borer resistance in the tiny fraction of "lingering ash" that remain healthy after 99% of trees have been killed. There is some hope that these might carry genes for long-term recovery.

What will Emerald ash borer mean for Oregon, ecologically? Oregon ash typically occurs in mixed hardwood forests, and is particularly abundant and ecologically important in riparian corridors. In the US generally there are 98 arthropods that are dependent on Fraxinus; and to date at least 17 species of arthropods (moths, beetles, mites) specialized on Oregon ash. So the loss of ash in Oregon would extirpate at least a short list of other species. The larger impacts will be at the plant community level. Oregon ash is a major component in riparian areas and wet meadows. If it is lost to Emerald ash borer, these forests will follow one of two (more likely both) paths: reorganization of the existing species (e.g., alder, cottonwood, and big-leaf maple), or colonization by other, perhaps exotic species. Either scenario entails systemic changes in the physical and biological attributes of once ash-rich forests.

Is there any way to fight back? What about natural enemies? Since the beginning of emerald ash borer era, scientists have looked at natural enemies of emerald ash borer in Asia; perhaps there are co-evolved species that effectively suppress Emerald ash borer in its native range? There are several good candidates, egg and larval wasp parasitoids (lethal agents that feed inside or on a host). These have been introduced at many sites in the east for >10 years. Results are mixed; introduced parasitoids do cause mortality, but only in a few cases have they shown the potential to actually decrease emerald ash borer populations. The other difficulty with a biological control approach is that success depends on many variables--tree size, weather, population density, dispersal conditions, etc. The climate of Oregon is another variable, which could increase or decrease the odds of success.

Pesticide treatments are another tool, with two principal applications. In landscape settings where individual trees have high value, pesticide treatment is in many cases more economical than removal. In natural areas, strategic use of treatment has been shown to slow the spread of EAB, giving the state more time to plan for widespread impacts. Of course there are environmental concerns; however the most effective (and expensive) treatment (emamectin benzoate) is a systemic material injected directly into trees, thus minimizing broader release into the environment.

Emerald ash borer and Oregon will be a new ecological experiment that may play out (badly) as it has in the east. But it is unknown how local conditions may change the trajectory. Major questions, and avenues of research: Does Oregon ash have useful genetic resistance to attack? How will emerald ash borer fare in a Mediterranean climate? Are there native natural enemies of related Agrilus that will attack emerald ash borer in Oregon? What role does ash play in Oregon forests, and what are the likely trajectories for a post-emerald ash borer scenario? In the meantime, any evidence of emerald ash borer is of great interest to the Oregon Dept of Agriculture - let them know!

What do I do if I find an emerald ash borer in Oregon? Early detection of new infestations will be critical to the state-wide response; the public can play a major role in surveillance. If you see a potentially infested ash, you can report it to the Oregon Department of Agriculture Invasive Species Hotline online or at 888-268-9219.

Some additional sources of information on Emerald ash borer and its impacts and control:

- Emerald Ash Borer in Oregon, Oregon Department of Agriculture

- Emerald Ash Borer Information Network

- Guidelines to slow the growth and spread of Emerald Ash Borer, Minnesota Department of Agriculture

-- David Cappaert is an entomologist with IAE who recently moved to Oregon from the eastern US.

Restoration

Research

Education

Contact

Main Office:

4950 SW Hout Street

Corvallis, OR 97333-9598

541-753-3099

info@appliedeco.org

Southwest Office:

1202 Parkway Dr. Suite B

Santa Fe, NM 87507

(505) 490-4910

swprogram@appliedeco.org

© 2025 Institute for Applied Ecology | Privacy Policy