by Mia Brann, July 2025

Slowly meandering the smooth curves of a trickling New Mexico ‘riíto’ (little river), our eyes are focused as they scan the banks for showy, purple flowers and kidney-shaped leaves. Our target, the northern bog violet (Viola nephrophylla) is the larval host plant for the Nokomis Silverspot butterfly (Speyeria nokomis nokomis), a threatened subspecies of the Silverspot butterfly that is found exclusively in Colorado, northern New Mexico, and east-central Utah. The butterfly can be found along streams or in wet meadows, a relatively rare habitat type in the Southwest that is being threatened by overgrazing and changes to hydrology. The remaining habitat is fragmented, leading to populations of butterflies becoming small and isolated. With the listing of this species, there is increased interest in identifying habitats with adequate populations of northern bog violet and nectar sources and taking steps to increase these floral resources to support the butterfly.

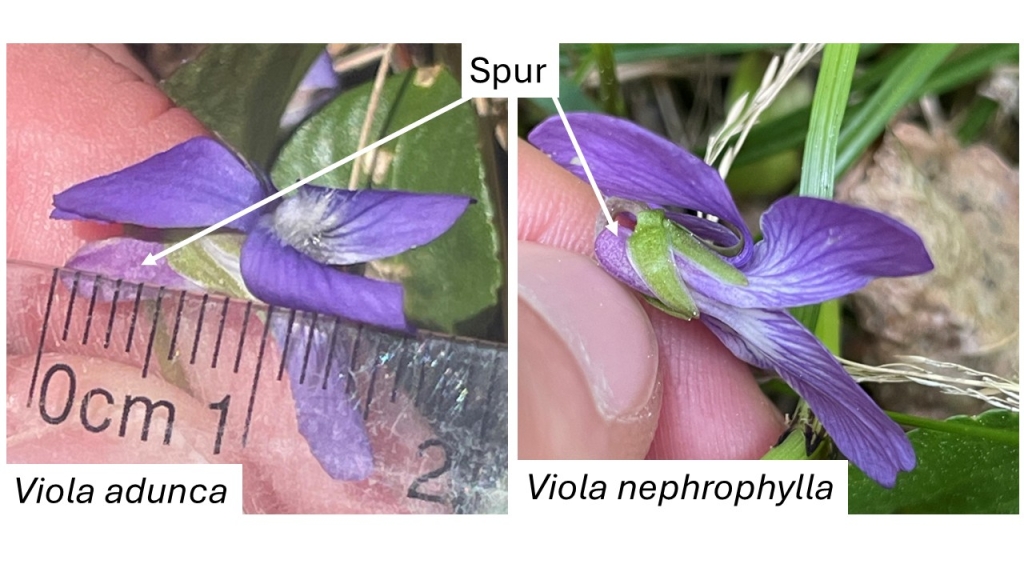

Using hand lenses, dichotomous keys, and a ruler, we scrutinize small botanical details. Before beginning field work, we understood there would be challenges to collecting seed from the northern bog violet – the first of which was positively identifying the plant. Northern bog violet is one of several common violet species in northern New Mexico, and one species, the hooked spur violet (Viola adunca), looks very similar to our target species. The two most important diagnostic characteristics between these species is the length of the nectar spur on the back of the flower (see photo below), distinguished by only a few millimeters, and the presence or absence of branching stems. This means that as we wander those riítos, we must carefully check the flowers and stems of the plants to ensure we are collecting the correct species. To further complicate things, these plants are no more than 30 centimeters tall and grow tucked between tall wetland grass species. No matter to us though, as a good day botanizing is not typically one spent fully upright!

The field season for bog violet population scouting began in mid-May this year, when the northern bog violet began its first flowering period. Bog violet uses two pollination strategies to produce seeds. It has bright purple flowers that you might imagine when you think of a violet, which are called perfect flowers. These flowers are insect pollinated and the seeds are typically the result of cross pollination between individuals in the population. The second flowering period occurs later in the summer and produces inconspicuous closed flowers, called cleistogamous flowers, that are self pollinated. In this type of pollination, all of the seeds produced represent the genetics of a single plant. With funding from the Carroll Petrie Foundation and Santa Fe National Forest, IAE is working to identify potential butterfly habitat by noting the presence and abundance of northern bog violet and other nectar species and scouting for populations of northern bog violet that can be targeted for seed collection. Within the next few years, we hope to utilize the seeds to augment priority habitat and create corridors to connect isolated populations. We are grateful to our funders and Southwest Region Forest botanists for proactively conserving this recently discovered rare Silverspot butterfly in our northern New Mexico forests and its charming, water-loving host plant.