Tagging monarchs in New Mexico

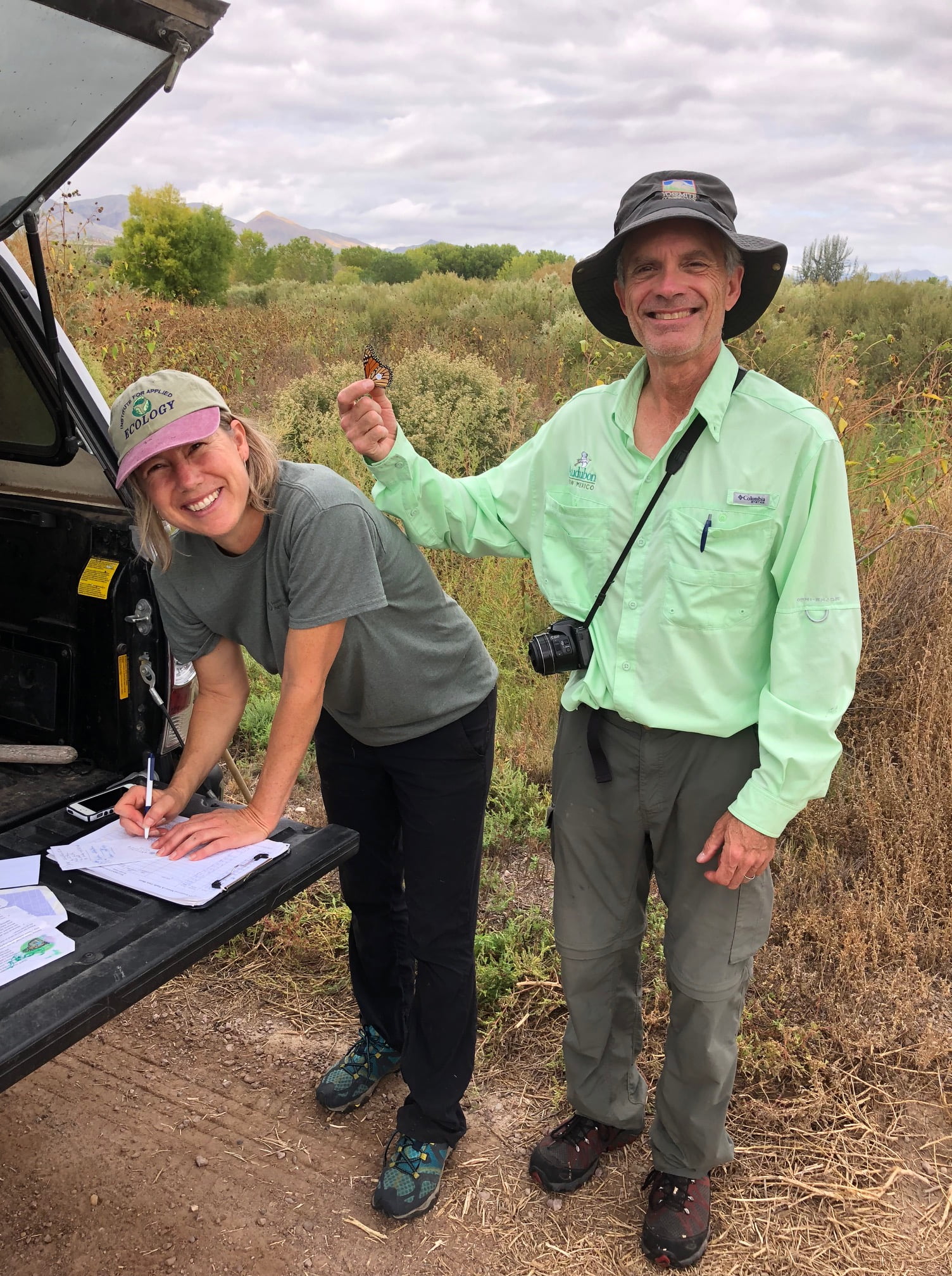

“I got one!” Steve Cary calls through a thicket of seep willow in full bloom. He’s netted a monarch butterfly on the Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in southern New Mexico. We convene at his pickup and get to work tagging this butterfly, a male with slightly tattered wings. It’s on a long migration to its wintering grounds and is already showing signs of wear.

Steve is the director of the Natural Resource Institute in Santa Fe, NM, a nonprofit organization he founded, and a member of the Technical Advisory Board for IAE’s Southwest Program. Melanie Gisler, the Southwest Program Director, and myself have joined him for an October morning tagging monarchs to better understand their migration patterns.

I gently lift a thin plastic disk, similar to a sticker used on fruit from the grocery store, from a sheet of pre-numbered tags and Steve places it on a wing of the monarch, then holds his thumb against it for several seconds to warm the adhesive so it sticks better. It may have a long ride.

Monarchs from western North America generally gather on pine and eucalyptus trees at several sites on the California coast to pass the winter months before flying north, while eastern monarchs form mass congregations in Mexico in the mountains of Michoacán. But no one knows for sure where monarch butterflies that summer in New Mexico overwinter. Some butterflies pass through the state from the eastern US on their way to Mexico, while others are “homegrown” and may head to Mexico also, or the California coast, or even overwinter in New Mexico in the warm, southern part of the state. It’s still not clear. And information on their migratory patterns is much needed, as recent research found only 300,000 western monarchs remain from a population of millions in the 1980s.

After tagging the monarch, Melanie sets it free to continue on its journey (watch the release video). Steve is aiming to contribute to the knowledge base of New Mexico monarchs (check out his white paper here) by tagging 500 every fall. We tagged two today. “Only 498 to go,” he says optimistically. The hope is that some of those tagged in New Mexico will be spotted in California or Mexico, or somewhere in New Mexico, helping to paint in a clearer picture of the whole journey of these remarkable, and declining, butterflies.

We run into other migratory butterflies while searching for more monarchs. Painted ladies. Buckeyes. Both are drinking nectar from seep willow (Baccharis spp.), which isn’t really a willow at all, but a shrubby relative of sunflowers with small but abundant flowers.

Monarchs use various flowering plants through the season as species come in and out of flower. At this time of year they have switched from sunflower (Helianthus annuus), which is now past peak bloom, to seep willow, which is in abundant flower. So we focus our search strategy for monarchs on seep willow stands.

Monarchs in New Mexico find abundant milkweeds in some areas, such as horsetail milkweed (Asclepias subverticillata) and showy milkweed (A. speciosa). Milkweeds are the only food source for monarch caterpillars, and this time of year they have taken to feeding on the last bits of green on the plants, which includes the outer skin of the fruits that contain white fluff and seeds.

With any luck, the butterflies that Steve Cary tags will be sighted in known wintering grounds in Mexico or California, or even in previously unknown sites in New Mexico, improving our understanding of this species and its conservation. Time will tell.

–Tom Kaye