By Lani DuFresne, May 2024

Spring is in full swing at IAE’s Southwest Office in Santa Fe, New Mexico, and almost all of the dozens of paper bags cluttering our shelves have disappeared in the past few months. These bags contain the unprocessed seed collections from last year, and over the winter we’ve been cleaning these collections and transferring them to our seed cooler for storage, where they wait to be distributed to our partners for restoration projects, research, and farm production. ‘Cleaning’ seeds means separating the actual seeds from unwanted plant material like stems and capsules, removing unfilled, insect-damaged, or otherwise unviable seeds, and getting an estimate of the number of actual seeds by weight.

From last year’s collections we’ve cleaned over 25 million seeds, a total weighing over 53 pounds and spanning 54 species of wild-collected and farm-produced plants native to the southwest. These are a wide variety of grasses and forbs collected across the ecoregions of New Mexico and Arizona, and the sizes and shapes of the seeds are as diverse as the plants themselves. As a result, the most challenging (and interesting!) part of the cleaning process is devising protocols to clean so many different seeds.

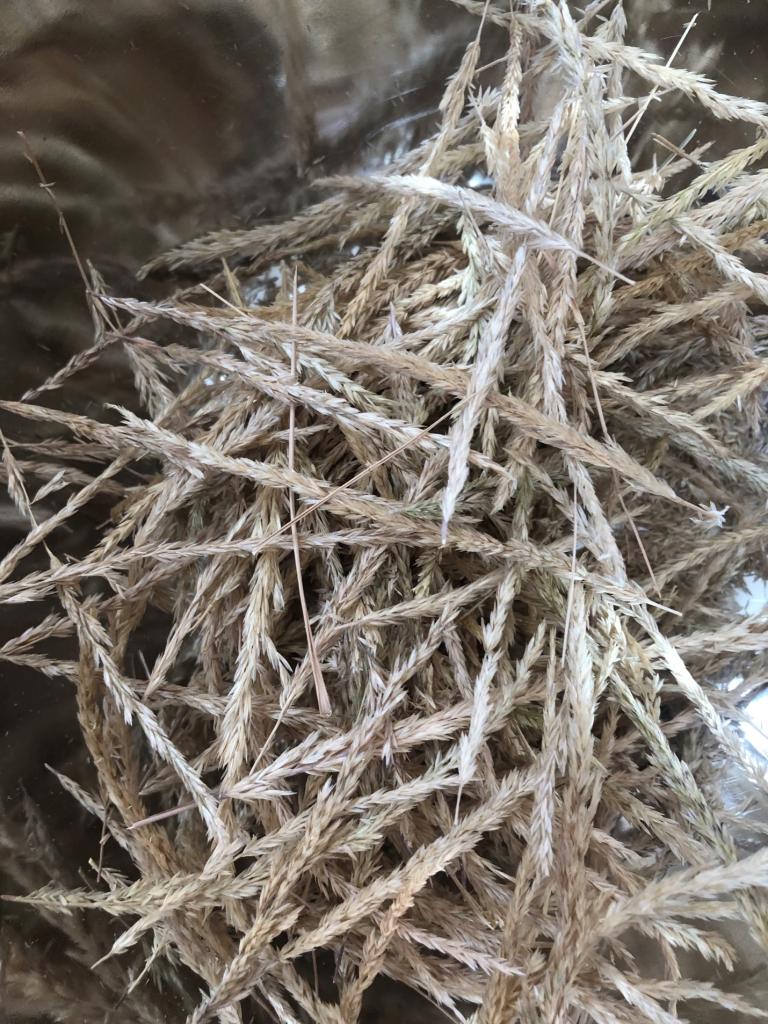

One of the largest seeds in our lab this year was the Rocky Mountain iris (Iris missouriensis), the average weight of which was 300 times that of one of the smallest seeds, sand dropseed (Sporobolus cryptandrus). Size is only one aspect of the visual diversity of seeds; the long, narrow inflorescences of Prairie Koeler’s grass (Koeleria macrantha) contrast sharply with the tiny, almost rock-like seeds of Scarlet Bugler (Penstemon barbatus). Cleaning these vastly different kinds of seeds means using our specialized machines creatively: some seeds are simply sieved and weighed, while others like the spear globemallow (Sphaeralcea hastulata) are run through different machines in several steps to get a final product of clean and viable seeds.

Seed cleaning can also be a communal process; volunteers have visited our seed lab for events every few weeks over the winter, where they helped clean both wild-collected and farm-produced seeds using handheld sieves and other manual tools. Our volunteers are often surprised at the variety of seed shapes and sizes, and always enjoy the experience of holding thousands of dropseed or beardtongue seeds in just the palm of their hand.

The many different seeds that have passed through our lab will end up in just as many different final destinations, but all of them will ultimately be returned to the landscape for conservation research and habitat restoration. Seed cleaning is one step in the process that brings us closer to these tiny instruments of our work before we send them on their way.

Thanks to all of our funders who supported seed collection and cleaning in the southwest in 2023, including the New Mexico Bureau of Land Management, Forest Service Region 3, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Carroll Petrie Foundation.